The Three Lucys of Contract Lore, Part Three: Peevyhouse vs. Garland Coal

Blog contributor Otto Stockmeyer is a Cooley Law School Distinguished Professor Emeritus. This is another in his series of posts offering a fresh look at famous cases.

The majority of the court decisions filling law school casebooks are merely illustrations and variations on a few leading cases. This series uses three leading Contracts cases to illustrate the point. Together they lay down fundamental rules regarding formation, consideration, and remedies (which is most of Contracts I). Back-stories cast doubt on the worthiness of some participants. Nevertheless the principles remain important.

The Case of Peevyhouse vs. Garland Coal

Most Contracts teachers begin the study of remedies with Hawkins v. McGee, the “hairy-hand case.” But to survey the landscape of contract remedies (damages, restitution, and specific performance), it is hard to beat the saga of Willie and Lucille Peevyhouse. (“Lucille” is the derivation of the name “Lucy.”)

The classic 1962 case of Peevyhouse v Garland Coal & Mining Co. involves breach of a coal strip-mining lease. The company failed to perform promised reclamation work on the Peevyhouse farm. The cost of reclamation was found to be $29,000. The jury awarded $5,000. On appeal (by the Peevyhouses) the Oklahoma Supreme Court reduced damages to the before-and-after diminution in the farm’s value, just $300.

These two measures of damages—the “cost” measure and the “value” measure—are both recognized by the Restatement (Second) of Contracts (Sec. 348(2)). Often they are approximately the same. But when they are wildly disproportionate, as in this case ($29,000 vs. $300), courts are reluctant to use the cost measure if it would result in a substantial windfall.

It appears that in awarding $5,000, the jury tried to settle upon a fair middle ground. Facing a claim for much more, the coal company considered the verdict a victory. In retrospect, the Peevyhouses should have taken the money rather than appeal. As Kenny Rogers cautioned, “You've got to know when to hold 'em, know when to fold 'em. . .”

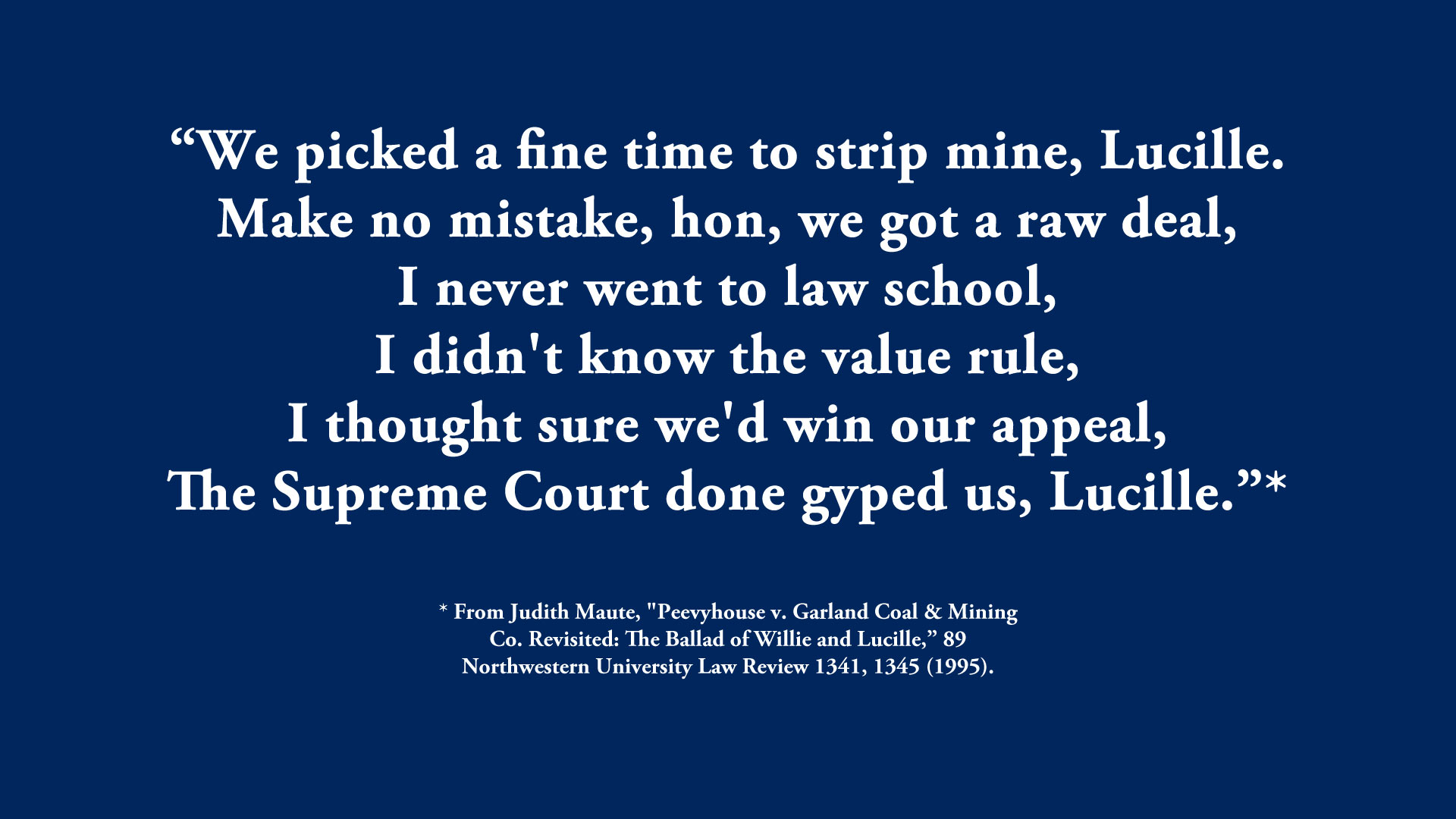

The Ballad of Willie and Lucille

In "Peevyhouse v. Garland Coal & Mining Co. Revisited: The Ballad of Willie and Lucille,” University of Oklahoma Law Professor Judith L. Maute reported on her study of the trial record. Instead of negligible damages, she believed that a restitution recovery could have amounted to anywhere from $3,000 (which the Peevyhouses waived in exchange for the promise of reclamation) to as much as $32,000 (the value of the extracted coal minus royalty payments).

The Restatement (Third) of Restitution and Unjust Enrichment (Sec. 39) would characterize Garland Coal’s breach as “opportunistic.” As such, restitution may be measured by the $29,000 saved by not restoring the land, sometimes called “negative” unjust enrichment.

Any of these measures of restitution would have greatly benefitted Willie and Lucille—by a factor of 10X or even 100X—over the $300 they were awarded (which was eaten up by litigation costs). And would have greatly benefited their lawyer, too, a personal-injury attorney who took the case on a one-third contingency basis. He ended up receiving no fee for bringing two lawsuits and three unsuccessful appeals over the course of six years.

Then there is the question of specific performance: a court order requiring the company to come back and restore the land. Specific performance would have guaranteed that the reclamation occurred, whereas damages need not be spent for their intended purpose. Failure to seek this remedy gave the impression that the Peevyhouses were just in it for the money.

Only after the damages lawsuit did their lawyer file suit for specific performance. The lawsuit was dismissed on the basis of res judicata (no second bite) and affirmed on appeal. We’ll never know whether specific performance might have been obtained if timely sought. The uncertainly can lead to a fruitful class discussion of the remedy’s parameters.

In a 2008 poll of law professors, Willie and Lucille Peevyhouse were voted “The Most Screwed Victims in Case-law History.” If so, it was not solely due to the coal company’s breach of contract. They were also victimized by a lawyer who lacked an understanding of how contract damages are measured and of the range of other remedies available. No student who studies the Peevyhouse case will commit such mistakes.

In a 2008 poll of law professors, Willie and Lucille Peevyhouse were voted “The Most Screwed Victims in Case-law History.” If so, it was not solely due to the coal company’s breach of contract. They were also victimized by a lawyer who lacked an understanding of how contract damages are measured and of the range of other remedies available. No student who studies the Peevyhouse case will commit such mistakes.

In addition to the bad luck of heavy spring rains that prevented reclamation while Garland’s earthmoving equipment was still on site—and the mismatch of being represented by a poorly-prepared sole practitioner going up against a big-city law firm—it turns out that two of the judges who sided with the Peevyhouse majority were later involved in a bribery scandal implicating counsel for Garland Coal. Screwed, indeed—every which way.

["Illustration from 'The Peevyhouses: The Most Screwed Victims in Case-Law History' posted to PrawfsBlog by Eric E. Johnson May 9, 2008."]

It may seem strange that such a tainted case is found in so many Contracts casebooks. It has been a favorite of law professors for more than 50 years because of its unique facts: the extreme disproportion between the cost of reclamation and diminution in land value. Memorable facts help students recall cases, and cases are the key to mastering common-law analysis.

To conclude this series:

The cases featured involve instances of avarice, villainy, and incompetence. Still, even bad characters can offer good lessons. Lucy v. Zehmer is key to an understanding of the manifestation element of contract formation although Lucy himself was a flim-flamer. Lucy Duff-Gordon’s infamy does not detract from the value of Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon in understanding consideration. A critique of Willie and Lucille’s outclassed lawyer in Peevyhouse v. Garland Coal serves to highlight the range of remedies available in contract disputes.

Although some of the cases’ principals have been sullied, their principles remain of enduring importance. Law students need to remember the Lucy Cases; it would be a rare final exam in Contracts I that didn’t implicate their doctrines.

During his teaching career, Professor Stockmeyer delighted in revealing the back-stories of cases he taught in class. Previous examples include The Adventure of the One-Dollar Diamond, Another Perspective on Dr. McGee, In Defense of Justice Morse and Confusion: Bad for Contracts, Good for Students?. Those and other blog posts are available here.

During his teaching career, Professor Stockmeyer delighted in revealing the back-stories of cases he taught in class. Previous examples include The Adventure of the One-Dollar Diamond, Another Perspective on Dr. McGee, In Defense of Justice Morse and Confusion: Bad for Contracts, Good for Students?. Those and other blog posts are available here.

Parts One and Two of this series are available HERE (Part One) and HERE (Part Two).