Kimberly E. O'Leary is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Cooley Law School, and co-author with Mable Martin-Scott of the book Multicultural Lawyering: Navigating the Culture of the Law, the Lawyer, and the Client. She is now retired from full-time law teaching, but continues to blog about multicultural lawyering and her travels with her husband, Paul, in the blog Rocinantes on the Road. Below is an excerpt from her blog story called New Zealand - respect, heart, & willingness to tackle the hard questions raised by multiculturalism.

We just completed our fourth trip to Aotearoa New Zealand, and every time we visit we learn more about this vibrant island nation. Everyone we speak to seems to recognize that all over the world, people are trying to figure out how to fashion a life where no one culture dominates the others. Even as Great Britain and the Commonwealth nations are crowning their first new monarch in 70 years, it is clearer than ever that the only way forward for Britain, and the world, is through respect and recognition of the multiple cultures that make up this planet.

In the United States, where we are from, our culture is trying to reckon with its own history of slavery, racism, and ethnic discrimination - but in my opinion, we're not very good at having that conversation. In Aotearoa New Zealand, the indigenous Māori residents suffered from overt discrimination for much of the 20th century. We admire the forthright manner in which Aotearoa New Zealand, as a country, has chosen to acknowledge its past and forge a future multicultural society encompassing respect for the multiple cultures that make up its modern-day society. But even in a society where by and large its citizens have big hearts, operate in good faith, and exhibit a willingness to make multicultural society equal and respectful, it is extraordinarily difficult to achieve. If the 1960s were characterized by a fight for equality across many parts of the world, our current time can be characterized as a conversation about what true equal, respectful multiculturalism looks like. It turns out to be harder than some of us thought.

People who live in Aotearoa New Zealand are proud of their multicultural heritage. When the Pātea Māori Club released its hit single, "Poi E", in 1984, the song shot to number 1 almost overnight. It also became well known overseas, especially in England. I just met someone in Suva, Fiji, who told me she knew the song and learned how to spin the poi balls in school. A Kiwi friend also learned to spin the poi balls in school.

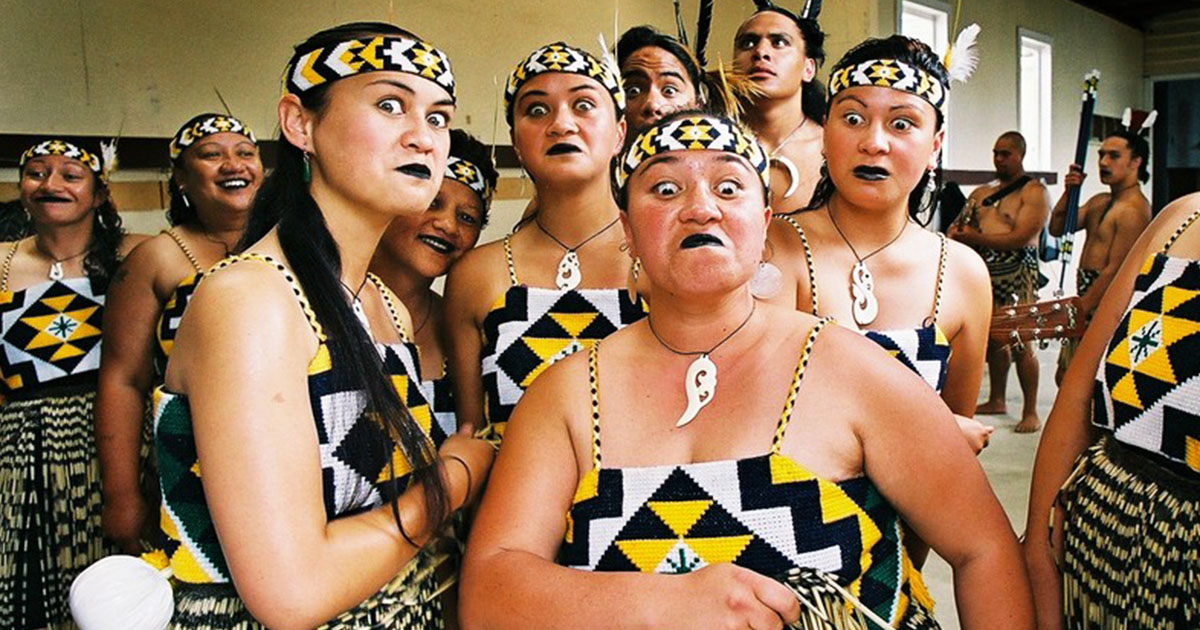

Written by Māori linguist Ngoi Pewhairangi and scored by Māori musician Dalvanius Prime, the song was performed by Prime's iwi in Pātea. The song became an emblem of Aotearoa New Zealand, and was described to me by both Māori and Pākehā as "the unofficial national anthem." The song is a source of pride for all Kiwis, but especially Māori. If you watch the music video, you cannot help but be caught up in the joy, pride and exuberance of the performers - from small children to older adults and everyone in between. The song meshed hip-hop (new at the time) with tradition, and was performed entirely in te reo Māori, according to traditional costumes and customs.

It featured women doing the poi dance, which is as much a female expression of love as the haka is a male expression of war. The video was a breakout moment of culture and identity in Aotearoa New Zealand, and representative of a more equal presence of Māori culture in the mainstream. The famous director, Taika Waititi, who included the song in his movie "Boy", said about the song:

I probably heard about it long before I heard it. But when I did I was hooked. Seeing Māori on TV was pretty rare so it wasn't until I saw the music video that I realized how huge and amazing it was. It's the quintessential New Zealand song. – Boy director Taika Waititi on seeing Poi E while growing up, https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/poi-e-1983.

Since then, Kiwis have worked toward developing true multicultural respect. When we visited in early 2023, a lot of people were talking about a concept called "co-governance." While the concept means slightly different things to different people, the basic idea seems to be that because Māori and Pākehā people were equal signatories to the Treaty of Waitangi, the management of certain national and regional issues should be conducted with equal input from Māori and Pākehā people.

Many of the Treaty of Waitangi land settlements have come with provisions for such co-management of resources such as water, forests, and the like. At least in the realm of natural resource management, there is a claim that international law requires such input by indigenous cultures. In addition to natural resources, which hold a special place in both the treaty and in Māori culture, this concept has been applied to the management of other national concerns such as Māori health services. The idea is controversial, and some people see it as an erosion of democratic principles of one person, one vote, because Māori people make up 16.5% of the population (compared to 71.8% Pākehā). Defenders of the idea say it is about administrative management, not legislative representation. But opponents believe it gives some Māori people more weight in policy. It is a vigorous debate and one that will not be easily resolved.

As an outsider, I have no firm opinion about these issues. They are complex and require a deeper understanding of the culture than I have. But I do have admiration for a society that actively engages in their debate. Coming to terms with the effects of colonial rule is not an easy task. Many societies shy away from discussing them. Australia is engaging in a similar debate about a Constitutional amendment which would give a "voice" to indigenous Australians guaranteed by the Constitution. They will be voting on that idea later this year. I've even recently seen the idea of co-governance used in the United States as a proposed reform in community policing (management of police co-governed by community governments and the populations they are most heavily policing). This is an idea we should all become familiar with.

So, hat's off to the small country with the big heart. We look to you for leadership on how to talk civilly with each other on important issues.