There's No Point in Having Dreams if You're Not Going to Fulfill Them

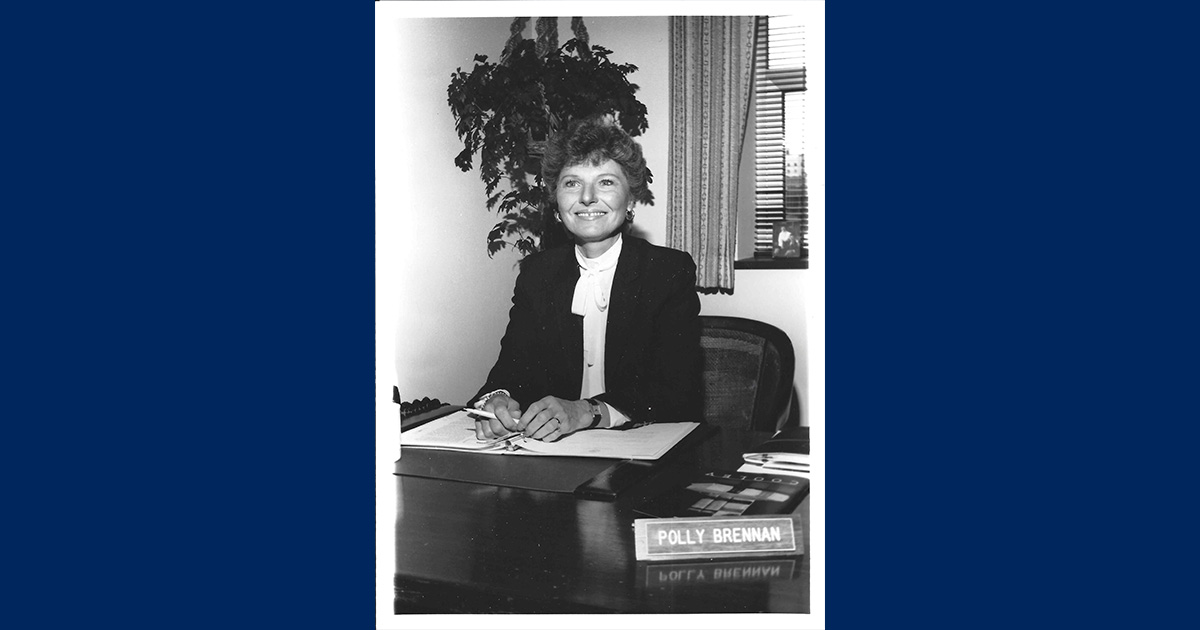

Pauline (Polly) Brennan was used to her husband, Tom — the late Michigan Supreme Court Justice Thomas E. Brennan Sr. — coming up with ideas — and plenty of them. Some were good, some not so good. “But some of his ideas were visionary,” she says, “And Cooley Law School was one of those.”

“He was always a dreamer. But he would also say that there’s no point in having dreams if you’re not going to fulfill them. And the school was a dream.”

Some might say that Cooley Law School may never have been more than a dream had it not been for the woman Judge Brennan referred to as his “sainted wife, Polly.”

Polly describes the time when the idea of starting a law school first began percolating in the judge’s head. “During the 1970s, competition for law school admission was fierce, a privilege for only the highest achieving, most elite students. I believe there were typically a dozen or more applicants clamoring for each law school seat,” Polly recalls.

As a member of the Michigan Supreme Court, Polly says her husband received multiple calls and letters every week from people asking if he could help them gain admission to law school. “People would tell my husband all they wanted was a chance. But the door to the legal profession was closed to so many people.

“Tom believed anyone who was willing to put in the work should at least have a chance to study the law,” Polly recalls. “He felt strongly that a legal education was something that should not be an exclusive opportunity for a select few. And he wanted to open the doors of the legal profession to non-traditional students and to people who otherwise didn’t have the opportunity to attend law school.”

In addition, all four of the state’s law schools were in southeast Michigan — three in Detroit, and one in Ann Arbor. Judge Brennan thought the state capital, in the heart of state government, was the ideal place for a law school.

Once he realized how important it was to expand the opportunity to study the law, Polly says he made a commitment to himself to make it happen. He filed articles of incorporation for a non-profit school, assembled a board of directors, and began recruiting the school’s first faculty, all while holding down his position as a member of the state’s highest court.

MAKING A DREAM A REALITY

Judge Brennan’s commitment still seemed like a pipe dream from the perspective of his wife, who was mostly worried about how the couple would provide for their six children. Shaking her head and smiling, Polly vividly remembers the car ride when her husband announced that he intended to make the law school his number one priority. “I was in the back seat of the car; our son John was driving, when Tom turned around and said, ‘You know what, Polly? I think I’m going to quit the court.’”

Polly was certain he was kidding. “I said, ‘Oh, right.’ But he said, ‘No, I’m serious. If I don’t go and work at this thing full-time, it’s not going to happen. We won’t get accredited. We’ve got 75 people who have made a commitment to Cooley and I owe it to them to make the school a success.’”

That night, after dropping their son off at school, the two stayed up until the wee hours in their hotel room working out how they could make Tom’s commitment to the fledgling law school a viable option for the couple and their family.

“It was around 4 o’clock in the morning,” Polly says, “we were sitting on the floor of our room at a Howard Johnson’s motel, when finally, I looked Tom in the eyes and we agreed, yes, we could do this.” From then on, Polly was just as committed to Cooley Law School as her husband.

On returning to Michigan, Judge Brennan scheduled a press conference to announce that he planned to resign from the Michigan Supreme Court at the end of 1973 to become the first full-time dean and president of Cooley Law School.

LEAP OF FAITH

Polly is the first to praise her husband for his total commitment to the law school, its students, and its graduates, but she also recognizes the dedication of everyone who took that leap of faith to bring the dream to fruition.

“Tom’s commitment was amazing, and not just his commitment, but the commitment of the students who signed up for the first class and the professors who signed on with him. They were all willing to take the chance.”

She recalled an interview she and Judge Brennan had with one of the school’s first professors, Prof. Ronald Trosty, and his wife, Fran, in New York City. Polly was amazed that Prof. Trosty was willing to pull up stakes and move to Lansing, all on Tom’s word that the school would succeed.

If you ask Polly what it was about her husband that gave others the confidence to follow his dream, she states with certainty that it was the strength of his professional achievements, certainly, but even more so, his character.

“He had served on several courts at that point,” explained Polly, “even as Chief Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court. Leaving the court to devote himself to the school demonstrated that he was serious. I think his actions impressed people and enabled people to believe in him.”

That faith and trust in Judge Brennan and the law school was rewarded at the first swearing in ceremony of the Cooley Class in 1976. Polly recalled the heartfelt pride of everyone involved that day.

“I was there to watch Tom and Bob Krinock, at the time the assistant dean, at the ceremony,” said Polly. “They were genuinely pleased, and certainly proud. That Cooley Class was incredible. They went into it with a ‘we’ll show you’ vengeance, and they did. That class had the highest bar pass rate in the state; they even beat U of M. What a great group of men and women.”

ONE INSPIRATION SPAWNS ANOTHER

The law school’s modest start blossomed into more successes, and many ideas. Polly laughed as she recalled the time her husband came home and declared that the law school needed some more pomp and circumstance at its commencement ceremonies.

“Polly, what we need for the graduation is marshals. They’re like ushers, but they’re called marshals. They should be dressed in attire that makes them stand out; with tails and striped pants for the men, and formals for the women — all gussied up!”

So, Polly took on the task of organizing the marshals program, a Cooley tradition that continues after 50 years.

FINDING AND RECRUITING TALENT

One of the first hires at Cooley started as Polly Brennan’s secretary, but that was only the beginning of Cherie Beck’s journey with Cooley Law School.

“I hired Cherie to be my secretary when I was working at the law school,” smiled Polly, “She had just graduated from Davenport College, and I didn’t know what to do with her. I never had a secretary before. But it didn’t take long to work into it. But when Tom’s secretary announced she was leaving, I knew how I could help him out.

“I went to his office and said, ‘You know what? I’m going to give you the best present I have ever given you, probably in our whole life, other than the children. I’m going to give you my secretary, Cherie Hadden. You won’t be unhappy. She is magnificent, and very organized.’ ”

Cherie Hadden Beck not only was a gift of support for Judge Brennan in the President’s Office since the beginning, but she went on to earn her bachelor's degree, then, with some encouragement from her boss, a J.D. from Cooley Law School. Today, Cherie Beck (Flannigan Class, 1999) is the Executive Assistant to the President, Legal Counsel & Corporate Secretary.

LEAVING A LEGACY AROUND THE WORLD

When asked what her hope is for the law school today, Polly says she hopes that the sense of community and warmth that started the law school would always be a part of what has made it so special. “I hope those good feelings where everybody’s pulling for each other, like family, never get lost.”

“Recently, I saw an article in the paper about the school and President McGrath’s leadership, and I’m so pleased to see that he is leading in the right direction,” she says. “It’s a comfort to know that Tom’s legacy is in such good hands.”

There’s one story that stands out to Polly as she considers her husband’s legacy and the impact he had on the lives of its graduates and the legal community.

“We were in an airport when a young couple approached my husband. They had a little boy, maybe two or three years old. The young man walked up to Tom and said, ‘Judge Brennan, I am a graduate of Cooley Law School and I want you to meet my wife.’ They talked for a while and exchanged many pleasantries, then the man leaned down and said to his little boy, ‘This is Judge Brennan; he’s the one who made it possible for daddy to go to law school. And that’s how all of this happened.’

“Tom had a sweet exchange with the youngster, just typical talk, then as we were getting ready to head to our gate, the little fella tapped Tom on the knee, looked up at him, and said in earnest, ‘I love you, Judge Brennan!’ I thought Tom would fall over. It was so endearing.”

Over 21,000 graduates later, the idea that Judge Brennan launched in 1972 still inspires people across the nation and around the world to pursue and fulfill their own dreams.

“Knowing people are able to pursue their love of the law is the greatest legacy of all,” Polly says.